Javier touched on Zombie Road back in 2009 when he did a story on the Paranormal Task Force.

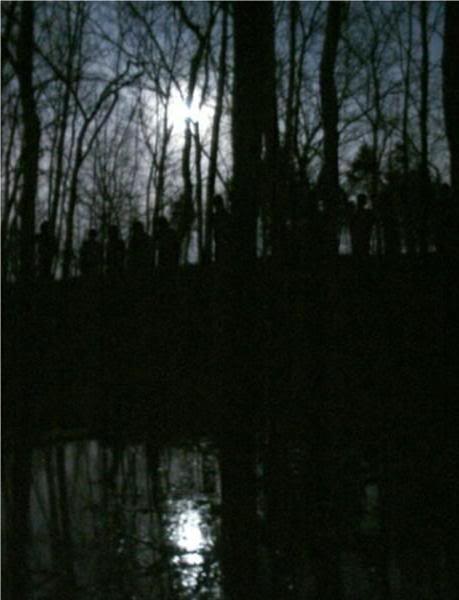

What caught my attention today was a photo of what appears to show several Shadow People standing along a tree line near what is deemed the most haunted road in America.

Located in Glencoe, Missouri, Lawler Ford Road, known as “Zombie Road” by the locals has a 100 year history of death and associated paranormal activity. For just a 2 mile stretch of forest road, it certainly packs a lot of punch weird-wise.

Here’s a good article on Zombie Road as well as some freaky photos:

ZOMBIE ROAD

The True Story of One of Missouri’s Most Haunted Places

The city of St. Louis is unlike many other major American cities. It is a large sprawling region of suburbs and interconnected towns that make up the metropolitan city as a whole, making it an impossible place to live if you do not own an automobile. With the Mississippi River as the eastern border of St. Louis, the settlers who came here originally had nowhere to go but to the west and the city expanded in that direction.

After all of these years, though, and despite the amount of construction and development that has occurred, once you leave the western suburbs of St. Louis, you enter a rugged, wild region that is marked with rivers, forests and caves. Traveling west on Interstate 44, and especially along the smaller highways, you soon leave the buildings and houses behind. It is here, you will discover, that mysteries lie…

There are many tales of strange events in the area, from mysterious creatures to vanished towns, but few of them contain any supernatural elements. The same cannot be said for another area that is located nearby. If the stories that are told about this forgotten stretch of roadway are even partially true, then a place called “Zombie Road” just may be one of the weirdest spots in the region.

The old roadway that has been dubbed “Zombie Road” (a name by which it was known at least as far back as the 1950s) was once listed on maps as Lawler Ford Road and was constructed at some point in the late 1860s. The road, which was once merely gravel and dirt, was paved at some point years ago, but it is now largely impassable by automobile. It was originally built to provide access to the Meramec and the railroad tracks located along the river.

In 1868, the Glencoe Marble Company was formed to work the limestone deposits in what is now the Rockwoods Reservation, located nearby. A sidetrack was laid from the deposits to the town of Glencoe and on to the road, crossing the property of James E. Yeatman. The side track from the Pacific Railroad switched off the main line at Yeatman Junction and at this same location, the Lawler Ford Road ended at the river. There is no record as to where the Lawler name came from, but a ford did cross the river at this point into the land belonging to the Lewis family. At times, a boat was used to ferry people across the river here, which is undoubtedly why the road was placed at this location.

As time passed, the narrow road began to be used by trucks that hauled quarry stone from railcars and then later fell into disuse. Those who recall the road when it was more widely in use have told me that the narrow, winding lane, which runs through roughly two miles of dense woods, was always enveloped in a strange silence and a half-light. Shadows were always long here, even on the brightest day, and it was always impossible to see past the trees and brush to what was coming around the next curve. I was told that if you were driving and met another car, one of you would have to back up to one of the few wide places, or even the beginning of the road, in order for the other one to pass.

Strangely, even those that I talked to with no interest in ghosts or the unusual all mentioned that Zombie Road was a spooky place. I was told that one of the strangest things about it was that it never looked the same or seemed the same length twice, even on the return trip from the dead end point where the stone company’s property started. “At times”, one person told me, “we had the claustrophobic feeling that it would never end and that we would drive on forever into deeper darkness and silence.”

Thanks to its secluded location, and the fact that it fell into disrepair and was abandoned, the Lawler Ford Road gained a reputation in the 1950s as a local hangout for area teenagers to have parties, drink beer and as a lover’s lane, as well. Located in Wildwood, which was formerly Ellisville, and Glencoe, the road can be reached by taking Manchester Road out west of the city to Old State Road South. By turning down Ridge Road to the Ridge Meadows Elementary School, curiosity seekers could find the road just to the left of the school. For years, it was marked with a sign but it has since disappeared. Only a chained gate marks the entrance today.

The road saw quite a lot of traffic in the early years of its popularity and occasionally still sees a traveler or two today. Most who come here now though are not looking for a party. Instead, they come looking for the unexplained. As so many locations of this type do, Lawler Ford Road gained a reputation for being haunted. Numerous legends and stories sprang up about the place, from the typical tales of murdered boyfriends and killers with hooks for hands to more specific tales of a local killer who was dubbed the “Zombie”. He was said to live in an old dilapidated shack by the river and would attack young lovers who came here looking for someplace quiet and out of the way. As time passed, the stories of this madman were told and re-told and eventually, the name of Lawler Ford Road was largely forgotten and it was replaced with “Zombie Road”, by which it is still known today.

There are many other stories too, from ghostly apparitions in the woods to visitors who have vanished without a trace. There are also stories about a man who was killed here by a train in the 1970s and who now haunts the road and that of a mysterious old woman who yells at passersby from a house at the end of the road. There is another about a boy who fell from the bluffs along the river and died but his body was never found. His ghost is also believed to haunt the area. There are also enough tales of Native American spirits and modern-day devil worshippers here to fill another book entirely.

But is there any truth to these tales and any history that might explain how the ghost stories got started? Believe it or not, there may just be a kernel of truth to the legends of Zombie Road – and real-life paranormal experiences taking place there too.

The region around Zombie Road was once known as Glencoe. Today, it is a small village on the banks of the Meramec River and most of its residents live in houses that were once summer resort cottages. Most of the other houses are from the era when Glencoe was a bustling railroad and quarrying community. Days of prosperity have long since passed it by, though, and years ago, the village was absorbed by the larger town of Wildwood.

There is no record of the first inhabitants here but they were likely the Native Americans who built the mounds that existed for centuries at the site of present-day St. Louis. The mound city that once existed here was one of the largest in North America and at its peak boasted more than 40,000 occupants. It is believed that the Meramec River and its surrounding forests was an area heavily relied upon for food and mounds have been found at Fenton and petroglyphs have been discovered along the Meramec and Big Rivers. It is also believed that the area around Glencoe, because of the game and fresh water, was a stopping point for the Indians as they made their way to the flint quarries in Jefferson Counties.

After the Mound Builders vanished from the area, the Osage, Missouri and Shawnee Indians came to the region and also used the flint quarries and hunted and fished along the Meramec River. The Shawnee had been invited into what was then the Louisiana region by the Spanish governor. Many of them settled west of St. Louis and were, for a time, major suppliers of game to the settlement. A family that lived at what later became Times Beach reported frequent visits from the Shawnee but the majority of the tribe moved further west around 1812.

Many other tribes passed through the region as they were moved out of their original lands in the east but no records exist of any of them ever staying near Glencoe. The reason for this is because the area was a pivotal point for travelers, Indian and settlers alike. The history of the region may explain why sightings and encounters of Native American ghosts have taken place along Lawler Ford Road. As we know that a ford once existed here (a shallow point in the river that was more easily navigated), it’s likely that the road leading down to the river was once an Indian trail. The early settlers had a tendency to turn the already existing trails into roads and this may have been the case with the Lawler Ford Road. If the Native Americans left an impression behind here, in their travels, hunts or quests for flint, it could be the reason why Indian spirits are still encountered here today.

The first white settler in the area was Ninian Hamilton from Kentucky. He arrived near Glencoe around 1800 and obtained a settler’s land grant. He built a house and trading post and became one of the wealthiest and most influential men of the period. It was mentioned that the area around Glencoe was a pivotal point in western movement. In those days, the Meramec River bottoms were heavily forested and made up of steep hills and sharp bluffs. The river flooded frequently and the fords that existed were only usable during times of low water. There were no bridges or ferries that crossed the river, except for one that was operated far to the southeast. The trappers and traders that traveled west of St. Louis, like the Indians before them, came on horseback along the ridge route that later became Manchester Road. It skirted the Meramec and was high enough so that it was not subject to flooding. Because of this, it passed directly by Hamilton’s homestead and the trading post that he established here. With the well-used trail just outside of his backdoor, as well as nearby fish, game and spring water, Hamilton’s post prospered.

Hamilton later built some grist mills near his trading post, which was a badly needed resource for settlers in those days. There are also legends that say that annual gatherings of fur trappers and Indian traders occurred at Hamilton’s place. These rendezvous have been the subject of great debate over the years but no one knows for sure if they occurred. It is known that his post was the last one leaving St. Louis and the first the trappers would see when returning, so it’s likely they did take place.

One of the mills that Hamilton started was later replaced by a water mill for tanning by Henry McCullough, who had a tannery and shoemaking business that not only supplied the surrounding area, but also allowed him to ship large quantities of leather to his brother in the south. McCullough was also a Kentuckian and purchased his land from Hamilton. He later served as the Justice of the Peace for about 30 years and as a judge for the County Court from 1849 to 1852. He was married three times before he died in 1853 and one of his wives was a sister of Ninian Hamilton. The wife, Della Hamilton McCullough, was killed in 1876 after being struck down by a railroad car on the spur line from the Rockwoods Reservation.

It has been suggested that perhaps the death of Della Hamilton McCullough was responsible for the legend that has grown up around Zombie Road about the ghost of the person who was run over by a train. The story of the this phantom has been told for at least three decades now but there is no record of anyone being killed in modern times. In fact, the only railroad death around Glencoe is that of Henry McCullough’s unfortunate wife. Could it be her ghost that has been linked to Zombie Road?

The railroads would be another vital connection to Glencoe and to the stories of Lawler Ford Road. The first lines reached the area in 1853 when a group of passengers on flat cars arrived behind the steam locomotive called the “St. Louis”. A rail line had been constructed along the Meramec River, using two tunnels, and connected St. Louis to Franklin, which was later re-named Pacific, Missouri. The tiny station house at Franklin was little more than a building in the wilderness at that time but bands played and people cheered as the train pulled into the station.

Around this same time, tracks had been extended along the river, passing through what would be Glencoe. The site was likely given its name by Scottish railroad engineer James P. Kirkwood, who laid out the route. The name has its origins in Old English as “glen” meaning “a narrow valley” and “coe” meaning “grass.

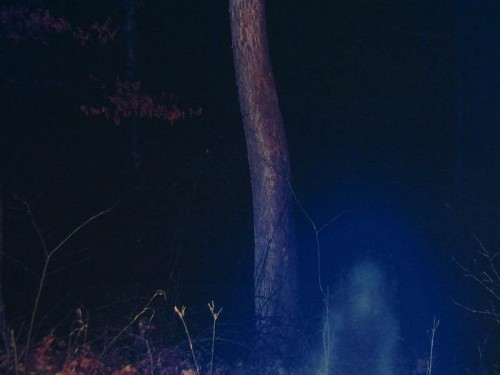

Only a few remnants of the original railroad can be found today. The old lines can still be seen at the end of Zombie Road and it is along these tracks where the railroad ghost is believed to walk. There have been numerous accounts over the years of a translucent figure in white that walks up the abandoned line and then disappears. Those who claim to have seen it say that the phantom glows with bluish-white light but always disappears if anyone tries to approach it. As mentioned, the identity of this ghost remains a mystery but despite the stories of a mysterious death in the 1970s, the presence is more likely the lingering spirit of Della McCullough.

One of the passengers who made the first trip west on the rail line from St. Louis was probably James E. Yeatman. He was one of the leading citizens of St. Louis and was the founder of the Mercantile Library, president of Merchants Bank and an early proponent of extending the railroads west of the Mississippi. He was active in both business and charitable affairs in St. Louis. He was a major force behind the Western Sanitary Commission during the Civil War. This large volunteer group provided hospital boats, medical services and looked to other needs of the wounded on both sides of the conflict. The world’s first hospital railroad car is attributed to this group.

After the death of Ninian Hamilton in 1856, his heirs sold his land to A.S. Mitchell, who in turn sold out to James Yeatman. He built a large frame home on the property and dubbed it “Glencoe Park”. The mansion burned to the ground in 1920, while owned by Alfred Carr and Angelica Yeatman Carr, the daughter of James Yeatman. They moved into the stone guest house on the property, which also burned in 1954. It was later rebuilt and then restored and still remains in the Carr family today.

The village of Glencoe was laid out in 1854 by Woods, Christy & Co. and in 1883, it contained “a few houses and a small store, but for about a year has had no post office.” At the time the town was created, Woods, Christy & Co. also erected a grist and saw mill at Glencoe that operated until about 1868. Woods, Christy & Co. had been a large dry goods company in St. Louis. There is a family tradition in the Christy family that land was traded for goods and materials by early settlers. This firm ceased operation as a dry goods company about 1856. While it is possible that some lands near Glencoe were the result of trading for supplies, the firm actually started a large lumbering operation around the village.

One of the many prominent St. Louis citizens who traveled through Glencoe during the middle and late 1800s was Winston Churchill, the American author who wrote a number of bestselling romantic novels in the early 1900s. One of his most popular, The Crisis, was partially set in St. Louis and partially at Glencoe. The novel, which Churchill acknowledged was based on the activities of James E. Yeatman, depicts the struggles and conflicts in St. Louis during the critical years of the Civil War. It is believed that Angelica Yeatman Carr was his model for the heroine, Miss Virginia Carvel. The first edition of the book was released in 1901 and was followed by subsequent editions. It can still be found on dusty shelves in used and antiquarian bookstores today.

In 1868, the Glencoe Marble Company was formed and the previously mentioned side track was added to the railroad to run alongside the river. The tracks ran past where the Lawler Ford Road ended and it’s likely that wagons were used to haul quarry stone up the road. Before this, the road was likely nothing more than an Indian trail, although it did see other traffic in the 1860s – and perhaps even death.

During the Civil War, the city of St. Louis found itself in the predicament of being loyal to the Union in a state that was predominately dedicated to the Confederate cause. For this reason, men who were part of what was called the Home Guard were picketed along the roads and trails leading into the city with instructions to turn back Southern sympathizers by any means necessary. As a result, Confederate spies, saboteurs and agents often had to find less trafficked paths to get in and out of the St. Louis area. One of the lesser known trails was leading to and away from the ford across the Meramec River near Glencoe. This trail would later be known as Lawler Ford Road.

As this information reached the leaders of the militia forces, troops from the Home Guard began to be stationed at the ford. The trail here led across the river and to the small town of Crescent, which was later dubbed “Rebel Bend” because of the number of Confederates who passed through it and who found sanctuary here.

After the militia forces set up lines here, the river became very dangerous to cross. However, since there were so few fords across the Meramec, many attempted to cross here anyway, often with dire results. According to the stories, a number of men died here in short battles with the Home Guard. Could this violence explain some of the hauntings that now occur along Zombie Road?

Many of the people that I have talked with about the strange happenings here speak of unsettling feelings and the sensation of being watched. While we could certainly dismiss this as nothing more than a case of the “creeps”, that overwhelming near panic that I described in an earlier chapter, it becomes harder to dismiss when combined with the eerie sounds, inexplicable noises and even the disembodied footsteps that no one seems able to trace to their source. Many have spoken of being “followed” as they walk along the trail, as though someone is keeping pace with them just in the edge of the woods. Strangely though, no one is ever seen. In addition, it is not uncommon for visitors to also report the shapes and shadows of presences in the woods too. On many occasions, these shapes have been mistaken for actual people – until the hiker goes to confront them and finds that there is no one there. It’s possible that the violence and bloodshed that occurred here during the Civil War has left its mark behind on this site, as it has on so many other locations across the country.

Visitors to Lawler Ford Road today will often end their journey at the Meramec River and the area here has also played a part in the legends and tales of Zombie Road. It was here at Yeatman Junction that one of the first large scale gravel operations on the Meramec River began. Gravel was taken from the banks of the Meramec and moved on rail cars into St. Louis. The first record of this operation is in the mid-1850’s. Later, steam dredges were used, to be supplanted by diesel or gasoline dredges in extracting gravel from the channel and from artificial lakes dug into the south bank. This continued, apparently without interruption, until the 1970s.

The gravel quarries were used the until the demise of the gravel operation in the 1970’s. The last railroad tracks were removed from around Glencoe when the spur line to the gravel pit was taken out. Some have cited the railroads as the source for some of the hauntings along Zombie Road. In addition to the wandering spirit that is believed to be Della McCullough, it is possible that some of the other restless ghosts may be those of accident victims along the rail lines. Sharp bends in the tracks at Glencoe were the site of frequent derailments and were later recalled by local residents. The Carr family had a number of photographs in their collection of these deadly accidents. It finally got so bad that service was discontinued on around the bend in the river. It has been speculated that perhaps the victims of the train accidents may still be lingering here and might explain how the area got such a reputation for tragedy and ghostly haunts.

Many visitors also claim to have had strange experiences near the old shacks and ramshackle homes located along the beach area at the end of the trail. One of the long-standing legends of the place mentions the ghost of an old woman who screams at people from the doorways of one of the old houses. However, upon investigation, the old woman is never there. The houses here date back to about 1900, when the area around Glencoe served as a resort community. The Meramec River’s “clubhouse era” lasted until about 1945. Many of the cottages were then converted to year-round residences but others were simply left to decay and deteriorate in the woods. This is the origin of the old houses that are located off Zombie Road but it does not explain the ghostly old woman and the other apparitions that have been encountered here. Could they be former residents of days gone by? Perhaps this haunting on the old roadway has nothing to do with the violence and death of the past but rather with the happiness of it instead. Perhaps some of these former residents returned to their cottages after death because the resort homes were places where they knew peace and contentment in life.

When I first began researching the history and hauntings of Lawler Ford Road, I have to confess that I started with the idea that “Zombie Road” was little more than an urban legend, created from the vivid imaginations of several generations of teenagers. I never expected to discover the dark history of violence and death in the region or anything that might substantiate the tales of ghosts and supernatural occurrences along this wooded road. It was easy to find people who “believed” in the legends of Zombie Road but I never expected to be one of those who came to be convinced.

As time has passed, I have learned that there is more to this spooky place than first meets the eye and that it goes beyond mere legends linked to old lover’s lane. For those who doubt that ghosts can be found along Zombie Road, I encourage them to spend just one evening there, along the dark paths and under the looming trees, and you just might find that your mind has been changed. As the famous quote from The Haunting states: “The supernatural isn’t supposed to happen, but it does happen.” And I believe that it happens along “Zombie Road”.

I’d like to thank my sources as follows:

Encounters With The Unexplained

Prairie Ghosts

Troy Taylor Books

Paranormal Task Force (more pics here)