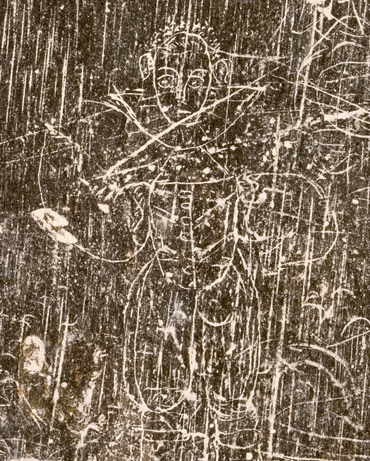

A simple drawing of a man is etched on a slate tablet recently excavated by archaeologists in Jamestown, Virginia, America’s first permanent English settlement.

A simple drawing of a man is etched on a slate tablet recently excavated by archaeologists in Jamestown, Virginia, America’s first permanent English settlement.

Breaking for a bit from the paranormal to the historical and mysterious I bring you this post.

I love history. Therefore it comes to no surprise that I was excited (well, not excited but intrigued) about the recent discovery of an early colonial-era tablet that has drawings of a human and birds, as well as some local flora and fauna. The tablet has on one side inscribed: “A Minon of the Finest Sorte“. and a more cryptic message: “EL NEV FSH HTLBMS 508,”

Anyone here a cryptographer?

Archaeologists in Jamestown, Virginia, have discovered a rare inscribed slate tablet dating back some 400 years, to the early days of America’s first permanent English settlement.

Both sides of the slate are covered with words, numbers, and etchings of people, plants, and birds that its owner likely encountered in the New World in the early 1600s.

The tablet was found a few feet down in what may be the first well at James Fort, dug in early 1609 by Capt. John Smith, Jamestown’s best known leader, said Bill Kelso, director of archaeology at the site.

If the well is confirmed as Smith’s, it could help offer important insights into Jamestown’s difficult early years.

(Related: “Jamestown Colony Well Yields Clues to Chesapeake’s Health.”)

Records indicate that by 1611, the water in Smith’s well had become foul and the well was then used as a trash pit. Archaeologists discovered the slate among other objects thrown into the well by the colonists.

Slate tablets were sometimes used in 17th-century England instead of paper, which was expensive and not reusable.

According to Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne’s curator, people drew games and wrote on broken roofing tiles, which could be washed off and used over and over again. “Inscribed slates from this time period are rarely found in England, so little is known about them,” she said.

(Also see National Geographic magazine editor Chris Sloan’s take on the discovery in his Stones, Bones ‘n Things blog.)

“A Minon of the Finest Sorte”

Archaeologists and other scientists are still trying to decipher the slate, the first with extensive inscriptions to be found at any 17th-century colonial American site.

The scratched and worn 5-by-8-inch (13-by-20-centimeter) tablet is inscribed with the words “A MINON OF THE FINEST SORTE.” Above the words are the letters and numbers “EL NEV FSH HTLBMS 508,” interspersed with symbols that have yet to be interpreted.

“We don’t know what it means yet,” Kelso said.

But there are some clues.

According to Straube, “minon” is a 17th-century variation of the word “minion” and has numerous meanings, including “servant,” “follower,” “comrade,” “companion,” “favorite,” or someone dependent on a patron’s favor. A minion is also a type of cannon—and archaeologists have found shot at the James Fort site that’s the right size for a minion.

Drawings on the slate depict several different flower blossoms and birds that may include an eagle, a songbird, and an owl.

“The crude drawings of birds and flora offer dramatic evidence of how captivated the English were by the natural wonders of the alien New World,” excavation director Kelso said. There’s also a sketch of an Englishman smoking a pipe and a man, whose right hand seems to be missing, wearing a ruffled collar.

Although the age of the tablet is not yet known, archaeological evidence—including turtle and oyster shells, Indian pots, trade beads, mirror glass, early pipes, medicinal jars, and military items—indicates that it was deposited in the well during the early years of James Fort, which was established in 1607.

If it’s Smith’s well, archaeologists believe the tablet could date to 1611, when the well was probably filled in, or earlier.

Another recent discovery from the same well is a brass baby’s toy that’s a combination whistle and teething stick.

Straube, the Jamestown curator, said the teething-stick portion is made from coral. In the 17th century, coral was considered good for babies’ gums and a magical substance that kept away evil. She said it may have belonged to one of the women who arrived with children in 1609.

Clues to the Slate’s Owner

It’s impossible to know yet who the slate’s owner—or owners—may have been.

Straube said an image that looks like a palmetto tree, normally found from South Carolina to the Caribbean (map), suggests that the drawings may have been made during the voyage from England to Jamestown through the West Indies, once a common route to the New World.

Or, she said, the slate could have been used by a colonist who was among about 140 castaways from the Sea Venture shipwreck in 1609. They were stranded in Bermuda for ten months and arrived at Jamestown in the spring of 1610.

Drawings of three rampant lions, used in the English coat of arms during the 1603-25 reign of King James I, have also been discovered on the slate and could mean that the slate’s owner was someone involved with government.

Archaeologist Kelso suggests the slate may have belonged to William Strachey, who served as secretary of the colony. He was among the shipwrecked colonists in Bermuda and arrived in Jamestown in 1610.

Straube, the curator, also said the tablet may have been used by someone living in Jamestown who died in the winter of 1609-10, known to colonists as the Starving Time, when the fort was under siege. Only about 60 of 200 people survived.

Near the slate archaeologists have found butchered bones and teeth from horses, as well as dog bones, that may date back to the infamous winter, when colonists resorted to eating their horses and dogs to survive.

It’s also possible that the tablet was used by more than one person. “There seems to be a difference in the style of handwriting,” Straube noted.

Layers of Writing and Images

The images on the tablet are difficult to see, because they are the same dark gray color as the slate and they overlap. The colonists would have written on the tablet with a small, rectangular pencil made of slate with a sharp point. This would have made a white mark—and fortunately for archaeologists today, it also left a scratch.

“You can wipe off the mark, but you can’t completely erase the groove,” Kelso, the archaeologist, said. “That’s why we have layer upon layer of drawings. In a way it’s archaeology. If one groove cuts across another groove, you could tell which one was the most recent.”

He hopes eventually to sort out the sequence of the images with the help of NASA, where scientists at the Langley Research Center are using a high-precision, three-dimensional imaging system similar to a CT scanner to help isolate the layers and provide a detailed analysis of the tablet.

Is It John Smith’s Well?

Determining whether this is in fact Smith’s well will be key to understanding Jamestown’s most difficult early years.

According to colonists’ accounts, water in Smith’s well became brackish within a year after it had been dug. Some experts think foul water, including some poisoned by salt water, may have been a major cause of death during the Starving Time, in addition to starvation and disease unrelated to the water, civil unrest, and battles with Indians.

Located near the James River, next to the first storehouse in the middle of the fort, the well was discovered last year, and archaeologists began excavating it earlier this year. They believe it was dug before a well dating to 1611, which is located farther away from the river.

Kelso said the colonists, having learned a difficult lesson from Smith’s well, would have dug their second well as far from the river as possible, to try to avoid contamination by the brackish river water.

Archaeologists have dug down 5 feet (1.5 meters) so far, and the pit has narrowed into a more well-like, circular shape, which may reach 9 to 15 feet (2.7 to 4.5 meters) into the ground.

Kelso said they won’t know for sure if it’s Smith’s well until they get to the bottom and date the objects there.

Finding the well, he said, “will give us a chance to really look at the health issue and figure out what spoiled the water.” Some clues to the mysteries contained in the 400-year-old slate might emerge then too.

Full source: News NatGeo

7 comments